The reasons why so many high-rise towers have faults

An explosive study into the poor quality of apartment buildings has found that new blocks are “plagued with defects”, with at least one found in 85 per cent of all buildings analysed.

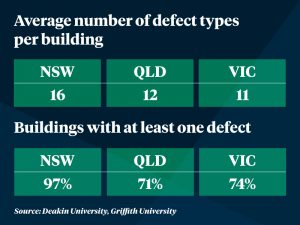

Written by Deakin University’s Nicole Johnston and Griffith University’s Sacha Reid, the report found 97 per cent of buildings in New South Wales had at least one type of defect.

The figures were also worryingly high in Queensland (71 per cent) and Victoria (74 per cent).

“The concern is not that defects occur, they are inevitable,” the report said.

“The concern is the extent, severity and impact these defects have on buildings and their occupants.”

Based on an analysis of 212 building audit reports, the authors found that water penetration and fire-protection defects were the most common, and that the average number of defect types in apartment buildings was 16 in NSW, 12 in Qld and 11 in Victoria.

The report’s publication comes amid a public outcry over the apparent poor quality of high-rise blocks, and follows the recent evacuation of Sydney’s Mascot and Opal Towers over structural defects.

What are the most common defects?

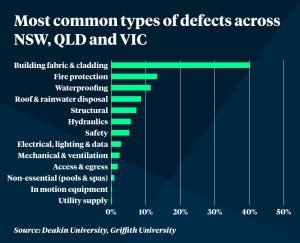

Most of the defects identified in the audits (40.19 per cent) were problems with the building’s fabric or cladding, followed by problems with its fire-protection systems (13.26 per cent), waterproofing (11.46 per cent), roof and rainwater disposal (8.58 per cent) and structure (7.25 per cent).

However, the report said roughly one third of the problems associated with the building’s fabric was caused by water penetration or moisture, meaning that problems with a building’s waterproofing and roof and rainwater disposal were likely underreported.

“The number of defects relating to fire safety are also alarming,” Dr Johnston said.

Affecting all aspects of the build, the defects ranged from damaged roofs and subsidence to exposed wiring and inconsistent emergency evacuation plans.

And they were found in numerous parts of a building, rather than one specific area.

Just under half of reported defects (43 per cent) were found in multiple locations, one in five (20 per cent) was found within units, and roughly one in six (16 per cent) was noted as external common property defects.

How did we get to this point?

The recent evacuations of Sydney’s Opal and Mascot Towers, coupled with the ongoing flammable cladding saga, have led to renewed scrutiny of standards within the construction industry.

But the concerns raised in recent weeks are nothing new.

Released in February 2018, The Shergold Weir Report shone a spotlight on the “serious compliance failures in recently constructed buildings” and drew attention to weak oversight by licensing bodies, state and territory regulators, and local governments.

Those involved in high-rise construction have been left largely to their own devices.’’ -The Shergold Weir Report, 2018

That report made 24 recommendations.

“The first recommendation of that report, and the first recommendation of the Opal Tower inquiry was to do something pretty simple: Make sure that engineers [and other building practitioners] are actually registered,” said Jonathan Russell, national public affairs manager at Engineers Australia.

“Because anyone can call themselves an engineer in NSW. It’s just not regulated at all.”

The national shift towards the private certification of buildings was also highlighted as a major problem.

The report said that it “carried with it an inherent potential for conflict of interest”, with certifiers tempted to pass non-compliant buildings as compliant in an attempt to secure future work from developers.

Builders Collective of Australia president Phil Dwyer couldn’t agree more with the Shergold Weir recommendations – though he has also called for a royal commission into the industry.

“You’ve got to have a policeman on the beat,” he said of the industry’s limited regulation and enforcement.

“There’s a real lack of training, and a lack of skill sets.

“The trade associations and the RTOs [registered training organisations] have these short courses – become a builder in six weeks – it’s just got to stop.”

In February, roughly two months after residents were evacuated from Sydney’s Opal Tower, the NSW government said it would support the majority of the recommendations included in the Shergold Weir Report.

It promised to appoint a Building Commissioner to act as the consolidated building regulator in NSW, and to introduce legislation requiring building designers and builders to be registered.

That legislation has yet to be introduced, but NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said on Monday that the reforms would be introduced to Parliament some time this week, in the hope of passing them by the end of the year.

“I want to assure everybody that the government not only has been working hard behind the scenes, but we hope to have the law changed by the end of the year,” Ms Berejiklian told reporters.

Artcile By Euan Black – The New Daily – Source Link